- Home

- Carrie Jones

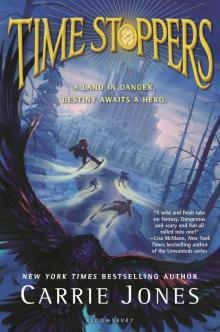

Time Stoppers

Time Stoppers Read online

For Emily Ciciotte, who believed in magic and

became a warrior, and for Shaun Farrar, who

was a warrior and became magic

Contents

1 The Wiegles

2 When a Grandmother Is a Monster

3 Trying to Be Good and Failing

4 Gnome Is in the House

5 Into the Wolf Pen

6 Running Away

7 Snowmobiles That Hover

8 Out the Window

9 Aurora

10 Eva the Protector

11 Miss Cornelia

12 Sweets

13 Aquarius House

14 Danger Approaches

15 Dinner

16 The Woman in White

17 The Letter

18 The Monsters

19 Preparing for Battle

20 Arms at the Armory

21 Evil Arrives

22 Hiding from the Horrible

23 Time Stops

24 Frozen Citizens

25 The Monster Book

26 Believe in Magic Skis

27 Trees and Skis Don’t Mix

28 Home Again

29 Dwarfs Are Tough Appetizers

30 Toppling Trolls

31 Cats to the Rescue

32 A Surprise Reunion

33 And So a Life of Crime Begins

34 Surrounded by Wolves

35 Sleigh Wolves

36 Gnome Home

37 A Celebration

1

The Wiegles

“Remember, you’re not special, Annie,” Mrs. Betsey told the small girl next to her as they stood on the rickety wooden step of the trailer. “Not special at all. So don’t go in there putting on airs, pretending you are above these people.”

Shivering in the Maine winter air, Annie Nobody wrapped her arms around her skinny body and her bright-yellow polka-dot parka that was a hand-me-up from her last foster home and was far too large around her middle but short in the sleeves. The last person to wear the jacket was nine years old. Annie was twelve; she seemed younger only if you didn’t peer closely enough at her to notice the sadness around her eyes. She cleared her throat and tried to sound patient. “I know, ma’am. You already told me that in the car.”

“What did you say?” From an oversize pink purse, Mrs. Betsey pulled out her identification card and official papers that proclaimed she worked for the state, placing young people without parents into homes. She clutched the papers so tightly her knuckles turned white. “Speak loudly enough so I can hear you.”

“I said ‘I know.’ I know I’m not special.” Annie spoke a little louder even though she didn’t want to say the words herself. It made them truer somehow.

“Good. So once again, may I reiterate that this is the last time I’ll be bringing you to a new family? I mean, really, dear. Is this your twelfth placement?”

Annie didn’t want to admit it, but it was. The first family had been the Farrars, who only wanted babies, and the mom refused to ever leave the house. Then when she’d turned two, she’d been sent to the Kerns family, who said that she was too pale and that Mr. Kerns’s boss wouldn’t promote him if his children weren’t good-looking. The Days moved to another state. The Wharffs didn’t like how dogs would follow her everywhere. Mr. O’Neill was sent to jail for assaulting a bartender. The Tierneys’ house burned down after their daughter cut Annie’s hair and left boxing gloves on the stove. The Pinkhams’ house burned down, too, after the rabbits started showing up in the heating vents. And so it went.

For as long as Annie could remember, she had been shuffled from one unloving foster home to another. The only constants in her life, for better or for worse, were the equally unloving Mrs. Betsey and Hancock County, Maine, which is where all her foster homes had been. Now, here she still was, this time in Mount Desert, a town with a split personality. In the summer, it was full of wealthy people from faraway places like Connecticut and New York, people with last names on plaques in front of libraries and museums. In the winter, those people went back to their real homes, leaving a town of a thousand or so laborers, lobstermen, teachers, artists, and scientists who worked at Jackson Lab in Bar Harbor. And, apparently, her newest foster family, Mrs. Wiegle and her son, Walden.

Annie couldn’t help staring at the Wiegles’ lopsided trailer with its dirty white paint and sky-blue trim. She shivered even more. Loud TV noises shook the entire structure. Dogs started yipping inside. Dogs! She loved dogs. Dogs licked you and wagged their tails and let you hug them. They never yelled at you or told you how un-special you were.

“It’ll be fine.” Annie’s voice turned cheerful and even a tiny bit louder. “I’m sure it will be great here. I think they have dogs.”

She stood there for a moment hoping she was right, but above her small frame, the evening sky turned a somewhat menacing color. Crows cackled in the distance. The trees that encircled the property drooped from the weight of the dirt and dust and snow. It seemed as if a good wind might topple the trailer down any second.

“Did you see the sky?” Mrs. Betsey ignored Annie’s answer. “It’s purple. How strange. There must be a storm coming.”

Something howled in the woods behind them. Annie scooted closer to Mrs. Betsey, who quickly shirked away, as if Annie’s touch would contaminate her immaculate clothes.

Something balled up inside Annie’s stomach and ached. It would be good to get this over with. “Did you ring the bell?”

“Of course, I rang the bell!” Mrs. Betsey lied and pressed the button for the doorbell. Her small eyes squinted at the sky. “What a strange sky … absolutely strange.”

Annie hopped from one foot to the other. Her duffel bag bopped against her shoulders. She glanced nervously into the woods. “Are you sure it’s the right place?”

“Yes, it’s the right place. Would I have walked you to the door if it was the wrong place? I’ve been here before. Mrs. Wiegle and her son are lovely. They seem perfect for you.” Mrs. Betsey shook her head. “If such a thing is possible. Now stop bouncing. You’re acting like a nervous rabbit.”

A nervous rabbit … Annie loved to draw animals—and rabbits especially—but she never thought she actually resembled one. Plus, the problem was that whenever she drew rabbits, or any animal for that matter, they seemed to randomly show up, which was always difficult to explain to foster parents. She eventually gave up trying.

That very morning (when Annie’s life began a whole new course and nothing could ever go back to the way it was again), Annie had packed her duffel bag one last time. Inside were the usual boring things: underwear, three pairs of socks, and two pairs of jeans. Also in it were her treasures. There was a journal, not of words but of pictures that she’d drawn when bored, plus several pencils she’d used so much they were merely stubs. There were also some pastel crayons a nice babysitter gave her once after a cranky foster sister at the Blands’ slammed a two-by-four on top of her skull. The headache was worth it for the special crayons. They made it feel like magic when she drew, like she was drawing with fairies. She’d rolled those crayons up in a pair of socks that she always kept dirty. That way no one ever found them to steal. No matter how bad the place was, no matter how bad the people were, no one wanted to touch dirty socks.

The people here wouldn’t, either, right? She pulled her bag a little closer to her, hugging it against her body.

“We’ve been waiting forever!” Mrs. Betsey announced, tapping the back of her heel against the step.

“Maybe they aren’t home,” Annie said. Sadness tightened her throat. “We could come back late—”

The door flew open, revealing a large woman wearing an incredibly tight T-shirt. An ugly boy’s face was screen-printed across the cotton/polyester blend. Annie’s mouth dr

opped open.

The woman gushed in a fake cheery voice, “Well, there’s our new girl. Oh, she’s pretty puny, isn’t she? Well, I hope she’s quieter than she looks.” She plucked the fabric of her T-shirt away from her chest so that they could see the face plastered across it better. “This here is my son, Walden. Isn’t he handsome?”

Mrs. Betsey poked Annie in the side with a long gel fingernail, urging her to remember her manners.

“Yes,” Annie blurted. “He is.”

“No falling in love with him. Only the most special girl can win my Walden’s heart.” Walden’s mother scrutinized Annie, her voice becoming much more stern. “You work hard and listen to your elders?”

Annie’s body shook. “Yes, ma’am.”

“Good. You’re not a whiner or the complaining type, are you? Not a chatterbox?”

“Um … I …” Annie hopped off the step and tiptoed backward toward Mrs. Betsey’s car. But Mrs. Betsey noticed and grabbed Annie’s elbow, pushing her up the stairs toward the trailer door.

A ghastly smile mortared itself to Mrs. Betsey’s face. “Mrs. Wiegle, so good to see you again. Here’s your Annie and your first check. I’m going to run. It appears as if it might storm. I’m sure you two will get along like hens to butter.”

Annie turned around, terrified, reaching out to grab the hem of Mrs. Betsey’s skirt, but the social worker had already scurried away, hopping into her car, shutting the door, and roaring off.

The taillights flickered as the car rushed over the bumps in the dirt driveway, and then she was gone. Annie was abandoned. Again.

Mrs. Wiegle hustled Annie into the kitchen and hopped around in a happy dance, holding the check from Mrs. Betsey in front of her like it was a waltzing partner. “Walden! Your new sister is here! And so is the first check!”

Walden heaved himself off the couch and plodded into the kitchen. He rubbed his hands together. “New gold mine, you mean. I can’t believe we’re getting paid for taking in this nothing, nobody of a girl. It’s almost too easy.”

He eyeballed Annie up and down as she stood by a crooked stove with a big scorch mark on the front. Six small dogs stopped yapping and all cuddled in next to her shins, like they were trying to protect her from Walden’s gaze. She bent down and picked up a poodle. He licked her face. She laughed and hugged him closer.

“The dogs like her,” Walden muttered. “The dogs don’t like nobody.”

“They’re nice dogs,” Annie said, voice shaking, as she studied the poop-strewn floor and the piles of trash in the corner. Doritos bags and candy wrappers clumped together into little litter mountains. Flies buzzed around everywhere. She shuddered, and the poodle licked her again consolingly. “What’s his name?”

“Little Mister Number One,” Mrs. Wiegle answered. “That one sniffing your shoe is Little Mister Number Two. Then the one pawing your pants is Little Mister Number Four. The others are Little Mister Numbers Five, Six, and Seven. We lost Little Mister Number Three to a couch-squishing incident a couple of weeks back.”

“Oh. That’s horrible. I’m sorry. Um … hi, Little Mister Number One,” Annie crooned, rubbing her nose against the dog’s nose. Little Mister wagged his tail.

“What kind of loser are you, kissing dogs?” Walden’s voice was disdainful, and he gawked at his mother. “What good is she? Shouldn’t they have given us someone better? Her voice is so light and fluffy and annoying.”

Mrs. Wiegle pinched Annie’s arm. “Tender.”

Annie yelped. Her skin already began to bruise.

Walden chomped on a Cheese Doodle–type snack. “I think we should send her back.”

“Who are you kidding? We finally actually got someone. It’s the dregs for us, and she’s the dregs,” Mrs. Wiegle said with a gleam in her eye. “This kid is no good, not special at all, and that means she’s perfect for us.”

Annie stared forlornly between the grimy slats of the trailer’s cheap vinyl blinds as the first few flakes of snow started to fall. Home sweet home, she thought. Again.

2

When a Grandmother Is a Monster

The snow fell hard that night. It fell hard and fast and quiet, as if it were trying to hide not just everything that was happening, but everything that was about to happen. It didn’t need to bother. On this particular cold December evening, Annie, the Wiegles, and most everyone else in the little village of Mount Desert was fast asleep. No cars zipped through the tiny mountain range that surrounded most of the town. The shops waiting for winter’s end were boarded up—all except for Gut’s, the tiny grocery, and First National, the bank. Even the local police station positioned at the bottom level of the Mount Desert Town Office Building was quiet and motionless.

One of the few Mount Desertans still awake that night was twelve-year-old Jamie Alexander. He lived with his father, Hercules, who scowled a lot, smelled like hate, and was currently working the night shift as a police dispatcher, and Jamie’s odd-acting grandmother, Alma. Jamie didn’t like to think about his grandmother, because thinking about her made him shudder all the way down to his bones. It was her teeth, maybe, and the way they seemed five sizes too large for her wide mouth. Or maybe it was just her voice and how it cackled and barked, more like an angry dog’s than a person’s.

None of Jamie’s friends, and not even Jamie himself sometimes, could quite understand how the three were related. Jamie didn’t resemble his father or his grandmother. He had much darker skin, a much shorter nose, and his bones weren’t the kind made for lifting heavy things. He figured he resembled the mom he’d never met and that she was probably African American. His family had only ever said one thing about his mother: she was dead, end of story. Jamie had always hoped there was more to the story, but he wasn’t sure. He wasn’t sure about much of anything except about how mean the Alexanders were and how worthless his life was, always doing chores, never having enough food, always being yelled at.

Most days, Jamie tried desperately to avoid both of them. But as everyone knows, it’s hard to keep away from the people you live with.

Though it was hours past his official bedtime, Jamie crept on his hands and knees across the icy floorboards of his house, making sure to sidestep all the creaky places. He had intended to sneak down to the kitchen to steal some food. He was always hungry, since his father and grandmother rationed his meals, only allowing him to eat canned meat—usually two cans of Vienna sausages per day. But a noise drew him to the bedroom window. He pressed his nose against the pane. As he stared down at the snowy lawn, his breath left him in a quick, excited puff and fogged up the window. He wiped a circle clean so he could see better. It appeared that he didn’t need to worry about sneaking around the bedroom. His grandmother wasn’t in the house at all. Instead, she was standing out on the side lawn. The wind whipped at her thin, gray hair, yanking it up in straggly strands, and her huge, misshapen bare feet were firmly planted in the icy snow. Jamie had never seen her feet before. She always wore hideous pink running shoes that he thought must be ten sizes too large.

“Why isn’t she wearing shoes?” he murmured. He shivered, partly from the thought of it and partly from the cold in his room. His father had duct-taped the radiators shut because he thought heat made boys’ bones weak. Jamie’s room was so cold he could see his breath make clouds in the air. He was too afraid to take the duct tape off. He was too afraid to do much of anything, usually.

Outside, his grandmother began stomping, which Jamie knew from personal experience was never a good sign. She seemed to be talking to herself. Against his better judgment, Jamie leaned an ear against the window. The cold snapped at him, sending splinters of pain through his skin. He couldn’t quite hear what his grandmother was mumbling. But he felt the tremor of something, many things, rattle up from the floor through the walls and window of his bedroom. The thudding vibrations of heavy objects in motion shook the house. And they were coming closer. His pulse rammed hard and fast against his skin as his grandmother clapped impatiently.

Jamie watched silently as fear froze his fingers against the windowpane. Twenty large, ugly people with bulbous noses emerged from the woods at the edge of the yard. They each stood about seven feet tall. They thundered across the property directly toward his grandmother. Jamie almost shouted out a warning, but something inside him, some tiny little nugget of common sense, stopped him.

His grandmother waved them along, and they rushed toward her, green skinned and so much larger than regular people. Their ears stuck out from their heads, and their hands were as large as tigers’ paws, with thick fingers that appeared as if they could smash rocks.

They weren’t people at all, Jamie realized, forgetting to breathe. They were monsters.

His grandmother jumped with excitement. The creatures caught up to her, and for a moment Jamie couldn’t find her among all the greenish-gray skin. Then he spotted her at the end of the line, even taller than normal, her skin tinted both greener and grayer. Her ears and nose had broadened, but it was her. He recognized her fluorescent-orange flowered housecoat and her cackling laugh as she ran off with the rest of the beast things into the dark night.

For a moment, Jamie knelt by the window in shock. His grandmother—his own grandmother—was one of those horrible, awful, scary-looking creatures. He wondered if it was a genetic condition or some sort of werewolf/vampire–style curse. That’s what happened in the horror movies his father loved. Vampires and werewolves bit people and turned them into monsters. He hoped that it was the latter because he had no desire to wake up one day supersized and greenish and howling.

“But she would have bitten me already if she wanted to, wouldn’t she?” he asked the quiet room, trying to reassure himself.

His stomach growled and Jamie stood up, suddenly realizing that he was alone in the house. He was alone in the house! He could go downstairs and eat something without being caught and punished. He rushed across the room, hauling open the door and racing into the hallway. He only wanted some crackers or cheese or something to stave off the hunger pains. Finally, finally, he could eat!

Entice

Entice Endure

Endure Need

Need Flying

Flying Captivate

Captivate Quest for the Golden Arrow

Quest for the Golden Arrow Girl, Hero

Girl, Hero Tips on Having a Gay (Ex) Boyfriend

Tips on Having a Gay (Ex) Boyfriend Enhanced

Enhanced Time Stoppers

Time Stoppers Love (And Other Uses for Duct Tape)

Love (And Other Uses for Duct Tape) Wolf's Hunger

Wolf's Hunger In the Woods

In the Woods After Obsession

After Obsession Endure (Need)

Endure (Need) Need np-1

Need np-1